Collection: Arabic American Actor Sayed Badreya. In The News.

SCENE NOW

Sayed Badreya's 'Jellyfish & Lobster' Wins BAFTA for Best Short Film

This prestigious award is the latest win for this touching dark comedy-cum-magical realism short. By Patrick Davies.Feb 19, 2024

Sayed Badreya's 'Jellyfish & Lobster' Wins BAFTA for Best Short Film

British short film ‘Jellyfish and Lobster’, starring Egyptian-American actor Sayed Badreya, won Best Short Film at the 2024 BAFTA Awards. The film had already received a host of international awards and nominations, with 11 of them being granted at the 2023 British Short Film Awards alone, including Best Supporting Actor for Badreya.

Following the release of the film, Badreya released a statement on his website, expressing his gratitude for the opportunity to play “as a man with Alzheimers, not a man with a gun,” referencing Hollywood’s proclivity to cast Arab men as terrorists and villains. “For almost four decades, I have been the angry Arab on the silver screen. But, once in a lifetime for actors like me, here comes a script that paints a new canvas that opens the door to different characters, and for that, I am thankful. Thank you for the opportunity to show the other faces of Arab actors.”

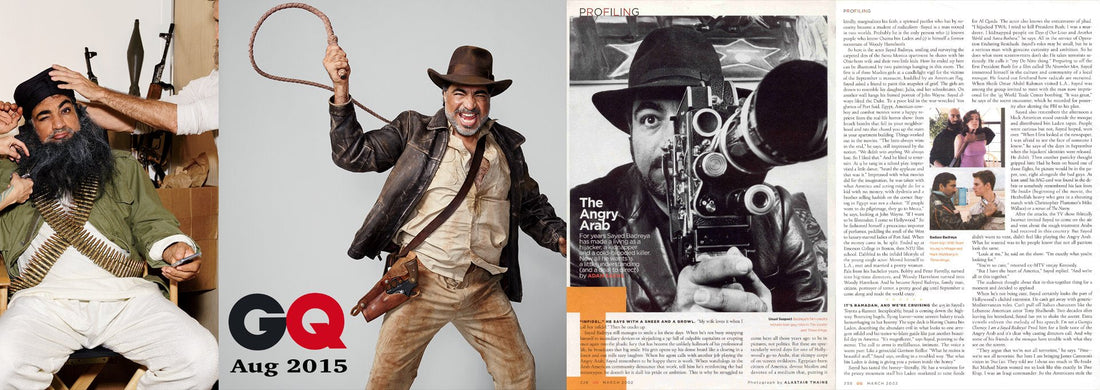

Actor Sayed Badreya in "GQ MAGAZINE"

You May Know Me from Such Roles as Terrorist #4

By: Jon Ronson - Photography By: Peter Yang.

August, 2015

Sayed Badreya on Muslim American Typecasting in Hollywood. Visit GQ MAGAZINE.

Arabic American Actor Sayed Badreya, Egyptian in Hollywood. In The News. Badreya won the Best Actor award from Action on Film Festival 2017

Badreya said to El Watan News, “I am extremely happy to receive this award, and happy that I performed in the movie the role of an Arab aviation officer within the American community, seeking to save the plane’s pilot from falling after an accident.”

Sayed Badreya is an Egyptian-American actor who was born in Port Said. Badreya has had only one dream since he was young; to travel to Hollywood and work in the cinema there. He fulfilled his dream by performing roles in great Hollywood films like ‘The Insider,’ ‘Three Kings,’ and ‘Independence Day.’ Before heading to Hollywood, Badreya studied acting in New York University Film School.

Sayed Badreya Is a Man of the People (www.moviemaker.com)

By Mallory Potosky on October 16, 2008

There’s so much more to Sayed Badreya than what appears on the surface. Born in Port Said, Egypt, the actor took a rather circuitous route to his current position in Hollywood as the go-to man for terrorist and doctor roles. “The most difficult time in my life when I was a little boy was the war,” Badreya explains of his beginnings. “I used to go and hide in the movie theater and be in love with American movies and America itself.” The plan was for Badreya to go to college, but after his father’s passing he was expected to work to help his mother support the family. It was while he was serving the country’s required military service that the future actor heard he was accepted to college in the United States. “So the deal was, ‘Okay, let me go to America for five years to study,’ because this was my dream.” He spent his first few years at the University of Massachusetts in Boston before studying film production at New York University. “The problem is, everyone in the class was using me as an actor. So I became really good at it,” Badreya says.

Five years turned into a few decades and by 2008 Badreya had carved himself a niche in the American movie landscape as Hezbollah Head Gunman (The Insider), Terrorist (in his own T for Terrorist) and Assisting Surgeon (Stuck on You). The stereotypical roles didn’t exactly ask him to challenge conventions but Badreya understands the system. “The stereotype is part of Egyptian film also,” he says. “If you look at Egyptian cinema they have a Black stereotype, a stereotype for foreigners and Jews. It’s everywhere.”

To counteract the prejudicial ideas prevalent both in the United States and abroad, Badreya co-wrote AmericanEast with director Hesham Issawi. “It’s a movie about your grandfather who came here in the beginning of time. It’s an Americana movie,” he says. “That was the most important thing—to put ourselves as Arab Americans in Americana, as an immigrant who came here as part of a community, like your grandfather—everybody’s grandfather.” The movie, which also stars Tony Shalhoub (“Monk”) as a Jewish immigrant, made its way around the festival circuit in the years since completion and the response was exactly what Badreya hoped for. “After the movie people were crying because they said, ‘My grandfather came from Germany and opened a restaurant and struggled. Now I’m watching him again in an Arabic skin.’

GQ March 2002

The Angry Arab

For years Sayed Badreya has made a living as a hijacker, a kidnapper and a cold- blooded killer. Now all he wants is a little understanding.

By: Adam Sachs

Sayed Badreya still manages to smile a lot these days. When he's not busy strapping himself to incendiary devices or skyjacking a 747 full of culpable capitalists or erupting once again into the jihadic fury that has become the unlikely hallmark of his professional life, he broadcasts that big smile. His grin opens up his dense beard like a clearing in a forest and out rolls easy laughter. When his agent calls with another job playing the Angry Arab, Sayed remembers to be happy there is work. When watchdogs in the Arab- American community denounce that work, tell him he's reinforcing the bad stereotypes, he doesn't let it dull his pride or ambition. This is why he struggled to come here all those years ago: to be in pictures, not politics. But these are spectacularly weird days for on of Hollywood's go-to Arabs, that skimpy corps of on-screen evildoers. Egyptian-born citizen of America, devout Muslim and devotee of a medium that, putting it kindly, marginalizes his faith, a spiritual pacifist who has by necessity become a student of radicalism-Sayed is a man rooted in two worlds. Probably he is the only person who (1)

knows people who know Osama bin Laden and (2) is himself a former roommate of Woody Harrelson's.

So here is the actor Sayed Badreya, smiling and surveying the carpeted den of the Santa Monica apartment he shares with his Ohio-born wife and two little kids. How he ended up here can be illustrated by two paintings hanging in his room. The first is of three Muslim girls at a candlelight vigil for the victims of the September 11 massacre. huddled by an American flag. Sayed asked a friend to paint this snapshot of grief. The girls are drawn to resemble his daughter, Julia, and her schoolmates. On another wall hangs his framed portrait of John Wayne. Sayed always like the Duke. To a poor kid in the war-wrecked '60s ghettos of Port Said, Egypt, American cowboy and combat movies were a happy reprieve from the real-life horror show: from Israeli bombs that fell in your neighborhood and rats that chased you up the stairs in your apartment building. Thing worked out in the movies. "The hero always wins in the end," he says, still impressed by the notion. "We didn't win anything, We always lose. So I liked that." And he like to entertain. At 9 he sang in a school play, improvised a little dance, "heard the applause and that was it." Impressed with what movies did for the imagination, he was taken with what America and acting might do for a kid with no money, with dyslexia and a brother selling hashish on the corner. Staying in Egypt was not a choice. "If people want to do pilgrimage, they go to Mecca," he says, looking at John Wayne. "If I want to be filmmsker, I come to Hollywood." So he fashioned himself a precocious importer of perfumes, peddling the smell of the West to luxury-starved ladies of Port Said. When the money came in, he split. Ended up at Emerson College in Boston, then NYU film school. Dabbled in the infidel lifestyle of the young single actor. Moved himself to L.A., met and married a pretty woman. Pals from his bachelor years, Bobby and Peter Farrelly, turned into bog-time directors, and Woody Harrelson turned into Woody Harrelson. And he became Sayed Badreya, family man, citizen, portrayer of terror, a pretty good gig until September 11 came along and made the world crazy.

IT'S RAMADAN, AND WE'RE CRUISING the 405 in Sayed's Toyota 4-Runner. Inexplicably, bread is coming down the highway. Bouncing bagels, flying loaves-some unseen bakery truck hemorrhaging its hot bounty. The tape deck is blaring Osama bin Laden, describing the abundant evil in what looks to one arrogant infidel and his traitor- to-Islam guide like just another beautiful day in America. "It's magnificent," says Sayed, pointing to the stereo. The call to arms is mellifluous, intimate. The voice a warm purr. Like a genocidal Garrison Keillor. "What he recites is beautiful stuff," Sayed says, smiling in a troubled way. "But what bin Laden is doing is giving you a poison inside the honey."

Sayed has tasted the honey-literally. He has weakness for the pricey mountain stuff bin Laden marketed to raise funds for Al Qaeda. The actor also knows the enticements of jihad. "I hijacked TWA ; I tried to kill President Bush; I was a murderer; I kidnapped

people on Days of Our Lives and Another World and Santa Barbara," he says. All in the service of Operation Enduring Residuals. Sayed's roles may be small, but he is a serious man with genuine curiosity and ambition. So he does what most screenwriters don't do: He takes terrorists seriously. He calls it "my De Niro thing." Preparing to off the first President Bush for a film called The November Men, Sayed immersed himself in the culture and community of a local mosque. He found out firsthand how radicals are recruited. When Sheik Omer Abdel Rahman visited L.A., Sayed was among the group invited to meet with the man now imprisoned for the '93 World Trade Center bombing. "It was great," he says of the secret encounter, which he recorded for posterity after alerting the FBI to his plan.

Sayed also remembers the afternoon a black American stood outside the mosque and distributed bin Laden tapes. People were curious but not, Sayed hoped, won over. "When I first looked at the newspaper, I was afraid to see the face of someone I know," he says of the days in September when the hijackers' identities were released. He didn't. Then another panicky thought gripped him: Had he been on board one of those flights, his picture would be in the paper, too, right alongside the bad guys. At least until his SAG card was found in the debris or somebody remembered his face from The Insider

(beginning of the movie, the Hezbollah heavy who gets in a shouting match with Christopher Plummer's Mike Wallace) or a rerun of The Nanny.

After the attacks, the TV show Politically Incorrect invited Sayed to come on the air and vent about the rough treatment Arabs had received in this country. But Sayed didn't want to vent, didn't feel like playing the Angry Arab. What he wanted was to let people know that not all patriots look the same.

"Look at me." he said on the show. "I'm exactly what you're looking for."

"You're so cute," retorted ex-MTV veejay Kennedy.

"But I have the heart of America," Sayed replied. "And we're all in this together."

The audience thought about that in-this-together thing for a moment and decided to applaud.

When he's not being cute, Sayed certainly looks the part of Hollywood's cliche'd extremist. He can't get away with generic-Mediterranean roles. Can't pull off Italian characters like the Lebanese American actor Tony Shalhoub. Two decades after leaving his homeland, Sayed has yet to shake the accent. Extra vowels enliven the melody of his speech: I'm not a Georgia Clooney; I am a Sayed Badreya! Prod him for a little tast of the Angry Arab and it's clear why casting directors call. And why some of his friends at the mosque have trouble with what they seen on the screen.

"They argue that we're not all terrorists," he says. "Fine we're not all terrorists. But here I am bringing James Cameron's vision in True Lies. They told me I shout too much in The Insider. But Michael Mann wanted me to look like this exactly. In Three Kings. I was an Iraqi commander. So the Americans stole the gold and they stole my prisoner and you wanna me to say thank you? No! I blow up something. That's my job." What that job will be like in a post-September 11 world is a question worth considering. The silence from his agent doesn't bother Sayed; he's pretty sure he knows more people in Hollywood than his agent does. His manger-well, he doesn't talk to the manager much. The Agency, on CBS, pay-dirt boon to silver-screen terrorists, calls him for December show ("I do a Yemeni guerrilla, but in a funny way"). What Sayed doesn't want to see come from the war is token roles. A few movies to make everybody feel better. He wants Arab-American actors to play all kinds of roles. The good news is the job market can't get any worse.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF POSITIVE FILMS for Arabs in American cinema: Anna Ascends, the touching tale of a working girl in an Arab-American coffee shop, came out in 1922. According to Jack G. Shaheen, author of the TV Arab and a study called Reel Bad Arabs: How Hollywood Vilifies a people, that's it. And the movie is now lost. Scanning a century of American cinema, shaheen can name eighteen films in which Arab-American actors play Arab-American roles. "Fourteen of those show us as clones of the negative Arab Muslim stereotype."

The retired professor-and grudging connoisseur of hijack dramas and Disney cartoons- is one of those critics in the Arab-American community who sometimes make life hard for Sayed Badreya. Friends at the actor's mosque were furious at him for his work in Executive Decision, even after he had his name removed from the credits. "Poor Sayed," says Shaheen from his home in Hilton Head, South Carolina. "I've cost him a few jobs." Sayed's days as a rakish kidnapper on Days of Our Live were cut short after Shaheen placed a call to NBC. Why, Sayed remembers wondering, were fellow Arab-Americans costing him a good paycheck? He was just beginning to have fun. Shaheen recalls the plot as typical of the popular view of Arabs as sinister, sex-crazed outsiders. "He kidnapped the blond and took her to some mythical Arab kingdom," he says "where she was going to have her head cut off unless she danced well or something like that."

Shaheen respects Sayed's efforts to educate Hollywood from the inside, but he remains skeptical of the impact an actor might have. "It's sort of Stepin Fetchit saying, 'OK, don't make me look too stupid," he says. And yet, though their philosophies are opposed, the critic and the actor envision a similar solution: Arab-Americans directing their own films. "Hollywood has only now allowed African-Americans to tell their story," notes Sayed. "If I compare myself with that, I am fine. Arab-American is crybaby! They really are. They have not paid for being foreigners." He points to community outcry over terror movies such as The Siege, in which, Tony Shalhoub plays a patriotic FBI agent. "The Siege wasn't that great, but it's someone's vision. They want someone to do a movie about Arabs and make them look good, and they don't want to

pay for it. If you want to write a movie about Arabs, something that's good, something that's sellable, do it. They say Hollywood is controlled by the Jews. Fine. It has nothing to do with that, but you can't tell them no. I don't believe Jewish control everything, I believe good product control everything."

Movies are Sayed's great love. Three-and-a-half-cent show at Cinema Misr in Port Said gave him his dreams, and dreams got him out of the ghetto. The subject of good product is personal. Better movies will mean not having to shoo away his daughter when Daddy is on-screen cranking a shotgun up Sean Young's trachea. Don't judge him for how long he is on the screen but for what he gets done in his time there. A clip from Three Kings flashes on TV. "Ahhh," he says, looking with a wistful smile on his own dead eyes. "The best-looking corpse in cinema."

THE MEN HE PLAYS ON FILM, the people who come to stir resentment in his mosque, the man whose voice is now filling the cooled air in the plush interior of the Toyota 4-Runner- they see the world in terms of holy war, and now Sayed must see it that way too. They've taken his religion-the proud code by which he defines his life-and turned it against his adopted home, his happiness, his American kids.

"They have hijacked Islam," says the actor. And in his small way, Sayed is determined to hijack something back. When he takes a role, no matter how limited, he tries to make it better. When he blows up at Christopher Plummer in the The Insider, that scene wasn't even scripted. He persuaded Michael Mann to let him act out. When he picks his kids up at school or sees a neighbor in the supermarket, he is an ambassador of his religion. He writes screenplays and puts them away until the time is right. He has used his own money to make a documentary called Saving Egyptian Film Classics in the hope of preserving the movies he grew up seeing. It is an unrequited love letter home. Egyptian declined the offer of help from U.S. Film archivers and labeled Sayed a troublemaker. When The Insider or Independence Day is shown in his native country, his scenes have been edited out. He persists.

We're driving to his mosque fir Friday-afternoon prayers. He parks several blocks away, to avoid traffic on the way out, he says, admitting that others do it for fear of reprisals. Inside the beautiful building, a Saudi prince's gift to the community, the mullah is talking about jihad. A different brand of jihad. One that stresses the necessity of letting non-Muslims know about Islam. Islam did not go Asia by sword, the mullah says. Its influence spread by the good publicity of its prosperous followers. This is Sayed's jihad. To take Hollywood not by force-not with protests and complaints-but with knowledge and charm.

"That's why I have a camera and not a gun," he says.

He's working on a screenplay now called Falafel City. It concerns an actor not unlike

him who has tried and tried to make movies with a positive spin on the lives of Arab- Americans. Turned down again, he takes radical action: He hijacks another movie and makes it his own. So far the real Sayed Badreya hasn't had to resort to force. He believes the months after September 11 will yield new roles for Arabs, new curiosity about those among us who live in two worlds. "I'm optimistic," he says. "Coming from where I come from, I have to be."

Asked if his friends in the mosque have forgiven him for his violent role in Executive Decision, he replies with a motto so American you could print it on the dollar: "Time make everybody forget; if not, they can eat shit."

A NATION CHALLENGED: HOLLYWOOD; Terrorist From Central Casting Has Hard Lessons to Teach

By LAURIE GOODSTEINDEC. 12, 2001

http://www.nytimes.com/2001/12/12/us/nation-challenged-hollywood-terrorist-central-casting-has-hard-lessons-teach.html

It could be the heavy beard. Or the accent evocative of an afternoon in a souk. Maybe it's his size, large enough to crush the average flight attendant.

Or perhaps because he can successfully convince an audience he will blow your head off, Sayed Badreya has made it in Hollywood by being cast in one role after another as an Islamic terrorist.

''Here, I am hijacking a T.W.A.,'' he said in his thick accent, hitting the play button on a video reel of his film clips in his Santa Monica apartment. ''Here, I am Hezbollah.'' Fast forward. ''This one, I am kidnapper.''

He is not as famous as his old roommate, Woody Harrelson, or his buddies from his starving-actor days, Peter and Bobby Farrelly, who recently cast him against type as a doctor in ''Shallow Hal.'' But he has done pretty well for the son of a street sweeper who first dreamed of being a movie star watching John Wayne and ''Spartacus'' in the theaters of Port Said, Egypt.

Filmmakers Shatter Arab Stereotypes in Hollywood

September 13, 200612:15 AM ET

Heard on Morning Edition

For a couple of decades in Hollywood, Sayed Badreya played stereotypical Arab bad-guy roles: a hijacker, a Hezbollah gunman and a murderous Iraqi tank commander.

But after the Sept. 11 attacks, he realized it was time to tell a story more like his own.

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6064305

GQ: You May Know Me from Such Roles as Terrorist #4

GQ: You May Know Me from Such Roles as Terrorist #4

The evening after our lunch in Westwood, I visit Sayed Badreya, the older Egyptian actor, at his Santa Monica apartment. When I arrive, he's online, looking at photographs of Arabian horses.

"I'm involved in breeding them," he says, "because I don't know if I can keep playing these same parts." He says his daughter was once asked at school what her father did for a living and she replied, "He hijacks airplanes."

Jun 23, 2016

AMERICANEAST is a 2008 American drama film about Arab-Americans living in Los Angeles after the September 11 attacks. The story examines long-held misunderstandings about Arabic and Islamic culture, and puts a human face on a segment of the American population about whom most Americans know nothing, but who today are of particular interest to them, either from curiosity or suspicion. The story highlights the pressures under which many Arab-Americans now live by focusing on the points-of-view of three main characters

17 - 23 May 2012

Badreya, now a successful and familiar figure on American movie screens, intended that when I interviewed him in the Al-ahram Weekly office during his short trip to Cairo, it should be included in the documentary, partly as a token of his admiration for his favourite national newspaper.

He grew up, he told me, in a poor alley in Port Said. His father died when he was nine years old. "My mother took the responsibility of raising nine young children on a social pension of only LE7 a month," he told the Weekly. "So after that I had to work in different jobs to help support myself." Yet this austere life did not stop him from watching films in the city's local cinemas. "This was always my passion. I always wanted to be an actor," he added.